Syrian refugee Fatima Hussein Al Ahmad, a mother of four, lives on a farm with 50 other workers in Sahba, Jordan. COVID-19 travel restrictions meant that didn’t work for two months in 2020, and feeding her family became a daily struggle.

Ms. Al Ahmad and her husband pick peaches and tomatoes, alongside other Syrians, Jordanians and migrant workers. When she was unable to work due to the pandemic, she was forced to rely on her own resourcefulness to survive.

I came to Jordan with my family, with my brother and sister. We came here from Syria so we can work and to escape the problems. I got engaged to my husband here and we got married in Mafraq.

We would work in one place for a month. Then we would have to move to a different farm. We were tired because of all the moving around. It was very difficult.

A settled life disrupted

When we came to this farm, they gave us a caravan. We found that living in a caravan is better than living in a tent and it is cleaner for the children and for us. We are now settled at this farm. We stopped moving.

I have four children. In the morning, after housework, I leave the children with a relative and go to work on the farm with the other workers. I work from 7am until around 2pm and then I go back home to my children, because I have a baby girl; this is why I can’t work a full day at the farm.

When we first heard about the coronavirus, we were scared. I started watching the news, going online on my phone, and going on YouTube to learn how to protect myself. We bought all the essentials, so we didn’t have to leave the house and mix with others.

At the beginning of the outbreak, we were told that we could not congregate at work. I stopped working for two months.

We went through a difficult time. We had to borrow money from people. We had expenses to pay for. As a mother, I had to secure an income to buy my baby daughter milk and to meet my children’s needs.

Adapting to a new reality

I started doing all sorts of work. I helped my husband and the farm owner to take care of the livestock, and in return I was given a small amount of milk, which I used to make yoghurt and cheese. I sold my products in the town of Sabha and then would go to the pharmacy to buy baby milk for my daughter.

I also faced a lot of pressure at home. I had to cook, clean and disinfect the house twice a day. In the first couple of months of the virus, we couldn’t obtain enough bread, so I was baking bread for the children every two to three days.

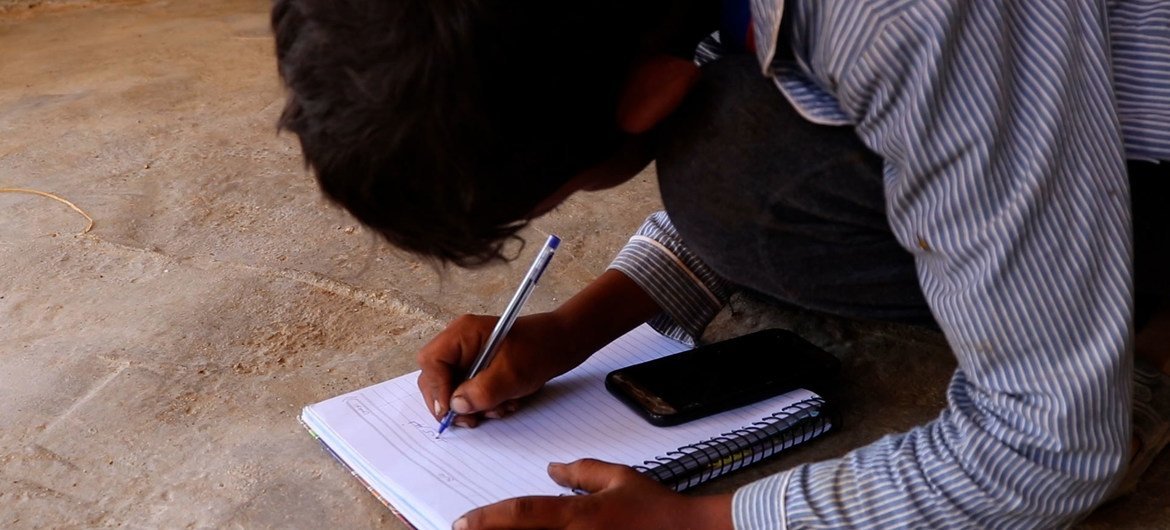

When the caravan school (informal education centre) opened at the farm our six-year-old son started going there and he was there for four months. Then they stopped going because of the crisis and they started giving them schoolwork remotely. He knows the letters and numbers and he knows how to write his name.

There is a lot of collaboration between neighbours. All the people here at the camp help each other and give each other things.

After the lockdown ended, we were glad to go back to work, so that we can secure an income to meet our needs and our children’s needs. We are happy to be back at work.

The impact of COVID-19 on the global workforce

- According to an ILO study, almost half of the surveyed workers who were in employment before the COVID-19 outbreak were out of work during the early weeks of the crisis. The majority did not have any forms of savings.

- The farm where Fatima lives is one of 24 farms being targeted by the ILO since 2018 to enhance decent working conditions in the agriculture sector.

- Activities include providing families living on site with prefabricated houses, setting up workers’ committees, helping improve occupational safety and health, skills training, and supporting access to informal education for children on farms.