Migrants and asylum seekers who enter Mexico through its southern border face abuses and struggle to obtain protection or legal status as a result of policies aimed at preventing them from reaching the US, Human Rights Watch said today. As leaders meet in Los Angeles for the Summit of the Americas, they should commit to ending abusive anti-immigration policies and to ensuring people seeking protection are received humanely in the US, Mexico, and elsewhere.

Refugee status applications and migrant apprehensions in Mexico have risen dramatically as US President Joe Biden has continued restricting access to asylum at the US southern border, and pushed Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador to heavily regulate travel to and within Mexico in order to prevent non-Mexican migrants from reaching the US. Those who cross Mexico’s southern border fleeing violence and persecution struggle to obtain protection, face serious abuses and delays, and are often forced to wait for months in inhumane conditions near Mexico’s southern border while struggling to find work or housing.

“Outsourcing US immigration enforcement to Mexico has led to serious abuses and forced hundreds of thousands to wait in appalling conditions to seek protection,” said Tyler Mattiace, Americas researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The Summit of the Americas is an opportunity for regional leaders, including presidents Biden and López Obrador, to commit to a regional migration agreement that moves away from heavy-handed enforcement policies and towards protection and human rights.”

Leaders from the Western Hemisphere are expected to sign a regional declaration on migration and protection during the Summit of the Americas, hosted by President Biden in Los Angeles. Any agreement signed should include commitments by leaders to restore and expand access to protection across the continent, to end heavy-handed enforcement policies that have led to abuses.

Mexico apprehended 307,569 migrants in 2021, the highest number ever recorded. A record 130,863 people also applied for refugee status in Mexico in 2021, the third-highest number in the world according to the United Nations refugee agency UNHCR. A decade ago, just a few thousand applied per year.

Most of those entering the southern border are Black, brown, and Indigenous people from Central America and the Caribbean who lack visas to enter Mexico. Nearly half of all asylum applicants in Mexico in 2021 were Haitians. Most enter near the city of Tapachula, in Chiapas state. Around 70 percent of those who apply for refugee status in Mexico do so in Tapachula.

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 100 migrants, asylum seekers, representatives of migrants’ rights groups and UN agencies, and officials from Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico, between August 2021 and April 2022, in person and by phone, in Tapachula and Mexico City, and in Tecun Uman, Guatemala, near the main border crossing.

Video, Israel, 24, Nicaragua

Most asylum seekers enter Mexico undocumented. Most said they came fleeing violence or persecution in their home countries but did not attempt to request protection at an official border crossing, fearing agents from Mexico’s immigration authority, the National Migration Institute (INM) would deport them. Most applied for refugee status once in Mexico. A few said they sought protection at the border and were turned away by INM agents or security guards. Many said INM agents dissuaded them from seeking refugee status in Mexico and pressured them to accept voluntary returns to their countries.

“I thought they would help us when we got to Mexico, but when we came to the border bridge and asked for protection they turned us away,” said one man who fled forced gang recruitment in Honduras. “I never thought I would have to leave my country. Now, I know if I went back, I wouldn’t last very long alive. If you don’t obey the gangs there, they force you to – or they kill you.”

In 2021, nearly 90,000 people applied for refugee status in Tapachula, equivalent to a quarter of the city’s population. Most wait many months for their applications to be reviewed and to receive documents proving their legal status and allowing them to leave. They often face discrimination, and struggle to find work and housing. Support programs by UNHCR and the Mexican government are insufficient. Some interviewees said they felt unsafe in Tapachula because it is close to the Guatemalan border, where the criminal groups they had fled were operating.

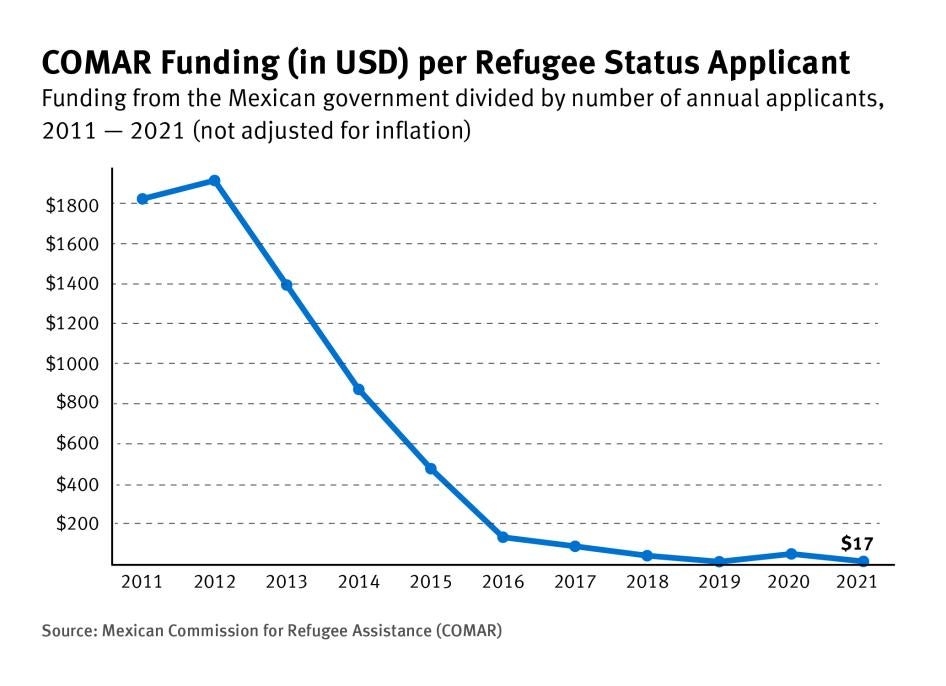

Mexico’s refugee system has been overwhelmed by the enormous growth in applicants. The budget for the refugee authority, the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR), which is separate from the INM, has not kept pace, and it has a growing backlog of refugee status applications. In 2021, it received more than 130,000 but only processed 38,005. UNHCR pays for many basic operating costs, including two-thirds of staff’s salaries. UNHCR contributed $4.5 million in 2021. The federal government contributed just over $2 million. State governments provide free space for some offices and refugee centers.

Most asylum seekers said they were fleeing death threats, extortion, and forced recruitment by gangs or drug cartels in Honduras, Guatemala, or El Salvador – or political persecution and generalized human rights abuses in Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela.

Senior INM officials said they do not believe most people seeking refugee status in Mexico have legitimate claims, either because they do not believe they are truly fleeing violence and persecution or because they believe most would prefer to seek asylum in the US. Mexican Foreign Relations Secretary Marcelo Ebrard has expressed similar sentiments publicly.

COMAR is able to review only some of the refugee status applications it receives. It grants protection to nearly all Hondurans, Salvadorans, and Venezuelans whose cases it reviews. But it rejects most applicants from Haiti, saying they do not qualify as refugees. COMAR officials have acknowledged that Haitians cannot be safely returned due to the severe security crisis there. The INM issued temporary “humanitarian” visas to about 50,000 Haitians in 2021. In 2022 it began a pilot program to allow 200 Haitian families who do not qualify as refugees to apply for residency in Mexico.

US President Joe Biden has continued many of former president Donald Trump’s abusive anti-immigration policies, including pressuring Mexico to stop migrants from reaching the US and blocking access to asylum at the US southern border through policies like Title 42 and Remain in Mexico. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has deployed almost 30,000 soldiers alongside National Migration Institute (INM) agents to apprehend undocumented migrants throughout Mexico.

Both the Biden and López Obrador administrations have a role in improving access to asylum procedures and the processing of refugee status applications in Mexico, Human Rights Watch said. The US should restore access to asylum at its border and stop pressuring Mexico to crack down on migration. Mexico should ensure that COMAR is properly funded and that asylum seekers are able to make claims at border crossings and from detention centers. Mexico should streamline processing of residence visas for those who have been recognized as refugees. And it should ensure that Haitians have access to protection and legal status.

“President López Obrador has often portrayed Mexico as a champion of migrants and asylum seekers,” Mattiace said. “If that is true, he should demonstrate it by ensuring asylum seekers in southern Mexico get a humane welcome.”