The conviction of a former Liberian rebel commander for wartime atrocities in Liberia by a French court is a milestone in delivering justice for victims, and for France’s efforts to hold those responsible for grave crimes to account, Amnesty International France, International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), and Human Rights Watch said today.

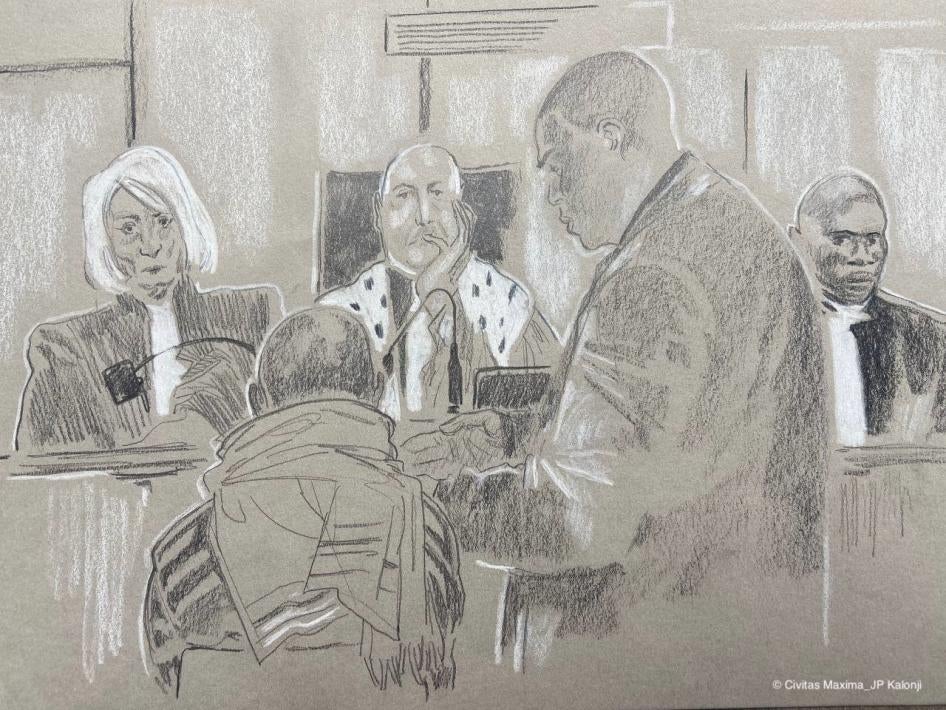

The Paris Criminal Court delivered its judgment for complicity in crimes against humanity, and complicity in and responsibility as a direct perpetrator for torture and “barbaric acts” in the trial of Kunti Kamara, also known as Kunti K., or CO Kunti, on November X, 2022. He is a former member of the rebel group United Liberation Movement of Liberia for Democracy (ULIMO), active during Liberia’s first civil war. The judges sentenced him to [life imprisonment]. Both the prosecution and defense have 10 days to appeal the decision. A hearing to examine a claim for compensation made by the civil parties will follow.

“More than 25 years later, the French court’s verdict is a ray of hope that justice is possible for the victims in Liberia,” said Elise Keppler, associate international justice director at Human Rights Watch. “The Liberian government should stop dragging its feet and request the UN, US, African Union, and other international partners to assist in setting up a war crimes court so more people implicated in crimes during the civil war can be held to account.”

During the trial, which lasted just under four weeks, witnesses described killings, rape, beatings, forced labor, and torture by ULIMO members. Some victims identified Kamara as physically involved in committing the crimes. Additional witnesses testified to the context in Liberia and to the psychological state of some of the other witnesses who testified to the crimes.

Kamara’s trial in person in France was possible because the country’s laws recognize universal jurisdiction over certain serious crimes under international law, allowing for the prosecution of these crimes no matter where they were committed and regardless of the nationality of the suspects or victims. The trial was the first in France involving grave crimes committed abroad that was not linked to the Rwandan genocide.

Convictions for war crimes, crimes against humanity, or torture during Liberia’s civil war era have been rare. Alieu Kosiah was convicted in Switzerland for war crimes in 2021, and the judgment is currently on appeal, and Charles “Chuckie” Taylor, Jr., son of the Liberian leader during that era, was convicted in the United States for torture in 2008. Kosiah was brought from Switzerland to France to testify in the Kunti Kamara trial.

Liberia has not attempted to prosecute a single serious crime among the widespread and systematic violations of international human rights and humanitarian law committed by all parties during Liberia’s civil wars. Charles Taylor was tried only for crimes in neighboring Sierra Leone by the UN backed Special Court for Sierra Leone.

Kamara was arrested in 2018, after the organization Civitas Maxima brought his case to the attention of French authorities. After two years of investigation, including a two-week fact-finding mission in Lofa County, northwest Liberia, where he allegedly led the local ULIMO faction, the French prosecutor accused him of various crimes. A question-and-answer document issued on October 5 offers more information on the trial and how it is situated in the context of Liberia’s civil wars and France’s use of universal jurisdiction.

“This trial on atrocities in Liberia is an important example of how France’s universal jurisdiction can offer a path for justice to victims,” said Jeanne Sulzer, head of the International Justice Commission at Amnesty International France. “Witnesses described extraordinary brutality for which Kunti Kamara was found guilty, including killings, rape, and torture .”

The use of universal jurisdiction in France is, however, restricted by several legal barriers, the groups said. These include the requirement that the accused must have “habitual residence” in France and that the crimes, even if prohibited under international law, must be explicitly punishable under the criminal law of the country where they were committed, except in genocide cases. In addition, unlike for other crimes in France, the Public Prosecutor’s Office has discretion over whether to prosecute, and French prosecutors must verify whether any national or international court has asserted jurisdiction before opening an investigation.

In contrast to Kamara’s case, a November 2021 decision by France’s Cassation Court annulled a Syrian crimes against humanity case because Syrian law does not explicitly criminalize crimes against humanity. The decision sparked renewed calls for reforms from civil society organizations and justice experts in France, including the Public Prosecutor’s Office. In light of these debates, the Cassation Court is expected to hold a hearing and issue a decision on the application of the restrictions in the coming months. Decisionmakers have indicated that the court’s ruling could help inform possible legislative reforms.

“The limitations on France’s universal jurisdiction laws are restricting access to justice for victims of the most serious crimes,” said Clémence Bectarte, lawyer and coordinator of the FIDH Litigation Action Group. “French authorities should bring their universal jurisdiction laws in line with their commitments to the fight against impunity for international crimes.”