UN Secretary-General António Guterres is headed to Colombia this week to mark the fifth anniversary of the signing of the peace accords that ended 50 years of conflict in the country, and his activities will include travel to the village of Llano Grande, where the townspeople and former combatants are working together to secure a better future.

This small village is an example of how, through peace and reconciliation – and determination – a new ‘family’ can be forged from among old enemies.

UN News traveled to the region ahead of the Secretary General, who’s two-day visit will begin Tuesday 23 November.

Familia Llano Grande reads a mural at the entrance of this Colombian town where ex-combatants, locals, soldiers and police coexist. This would have been unthinkable just five years ago, before the peace deal was reached that brought an end to the conflict between the Colombian Government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, known as the FARC EP.

Family, of sorts

All sides consider themselves victims of a conflict that lasted too long. They are now a “family” of sorts. One that has had its ups and downs, and wounds that need healing, but which in this case, the United Nations is helping through what could be called ‘reconciliation therapy’.

Peace “has brought many benefits for the peasants, for the communities, for the public force. Mainly for the Llano Grande family. We take care of each other, we meet, we see how we can help each other,” says a member of the small contingent of the Army, stationed on the side of the mountain where Llano Grande is located, and who preferred not to give his name.

“Oh yes, now we are a family,” said 67-year-old Luzmila Segura, who remembered that during the, she woke up on many mornings filled with fear.

“You saw the armed people arriving. Oh, how scary! My God! We thought they were coming to kill us,” she recalled, adding that armed guerrillas attacked the mountainside village “many times” and even ransacked her small ranch in the countryside and burned everything in sight. She was forced to leave her farm and go to live to a nearby village.

But since the peace deal was signed, Ms. Segura said, smiling: “Now I feel very happy because they gave me the house. Now it’s very calm here. We all work together as a family. Peace has [held] and so far, everything is going well. All together. It has already taken away my fear.”

She now works at a new Arepas factory, started with the help of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

We are all ‘working for peace’

Carmen Tulia Cardona Tuberque, who runs the Arepas factory where Ms. Segura works, says she prefers to talk about the present because the past too painful. She shies away from the details of her personal story that includes a husband who was killed in the conflict, a sad refrain echoed by many who stayed in Llano Grande, as well as those who fled.

“I believe this is a community that, despite so many difficulties that it has been through, today has everyone together working for the same cause, peace. You never thought this was going to happen,” she said, looking plaintively out at the horizon.

“The community contributes a grain of sand to the people. We, here as a community, support each other, because harmony depends a lot on that,” she continued, her face lighting up a bit as she added that many people displaced by the fight are returning to Llano Grande. “That is something that motivates you a lot.”

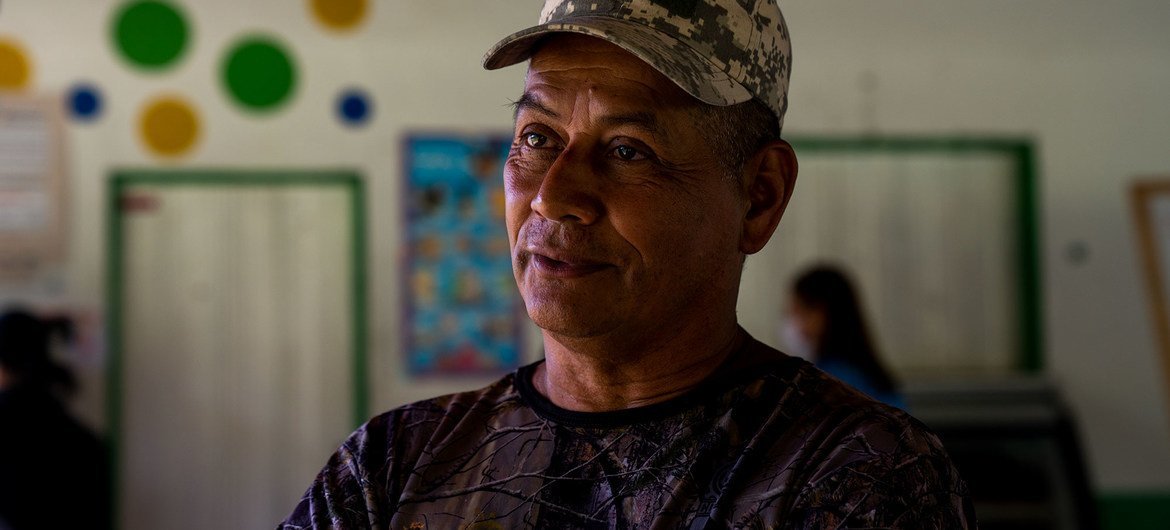

Similarly, Jairo Puerta Peña, a former combatant who joined the FARC when he was 14 years old, “around 45 years ago”, who now attends a training course in construction, said he also feels he is part of the Llano Grande family. “We all have the same goals: To live better, to work with peace of mind.”

After his morning training class wrapped up, Mr. Peña detailed how his life has changed in the past five years: “Life in war was always walking, knowing, talking to the population, studying and training the troops so we would not be killed when we had to face the enemy. After the Peace Accords, life has been calmer. There is peace of mind … being with family, sleeping, eating, working … The shots, the bombs and the helicopters loading troops are no longer heard.”

An ex-combatant’s struggle for a ‘normal’ life

Mr. Peña’s friend and fellow ex-combatant, Efraím Zapata Jaramillo, who was 21 years old when he left his construction job in Medellín and “went up the mountain” with the FARC in the department of Caquetá, explained how he went from being in the mountains with a rifle to struggling to reintegrate into society “and have a normal standard of living, like any Colombian.”

“All of us here, ex-combatants, non-combatants, the police and the Army, are a family fighting for peace to move forward and not take up arms again. The word should be our weapon; [and we should use it] to not only defend our rights but also those of the Colombian people. Especially the peasantry, who have been abandoned by the State,” he says, sitting in front of the sewing machine which he uses to make garments for the community, thanks to assistance from the UN Development Programme (UNDP).

Sitting next to him in the tailoring workshop is Monica Astrid Oquendo, a young peasant woman for whom the Peace Accords have brought not only peace of mind, but many opportunities to learn and train in ways that have benefited the community so much.

“We are like a family because we share ideas, we share work,” she says.

With a measuring tape hanging around her neck, Ms. Oquendo is excited about the handcrafted sweatshirts and polos she has made, and the windbreakers she is learning to construct. They will be sold in the valley and beyond, to protect motorcycle riders from the sun, rain and cold.

A village teacher helps build a family

When it was announced that 117 ex-combatants were going to be relocated to Llano Grande for their reintegration, Mariela López, a teacher at the town’s school, felt fear, but had few doubts about what she thought was best for Llano Grande and Colombia as a whole.

“That first day that I saw them again, I left. I went to town and down there, I sat down to cry. I said, how can I talk about peace if I have not forgiven? But if I do not forgive, then the one who is hurting is me. And I said to myself I don’t want any family in Colombia to live what I experienced, and from today I am going to contribute whatever it takes so the peace process can take place and so reconciliation can be experienced in Llano Grande,” she explained.

Later, when she met the ex-combatants, she changed his opinion of them: “We thought, and not only me, that ex-combatants were aggressive people because of what we had experienced, but when they arrived, then I thought they are not so bad and – I am going to apologize for what I am going to say – I think that many of them are also victims.”

The UN lends a hand

Located in the department of Antioquia, Llano Grande is a village of 150 inhabitants. It is also the site of one of the Territorial Spaces for Training and Reincorporation, which facilitate the reintegration of ex-combatants into civil society, while benefiting the surrounding communities.

It is located on a property that was bought and handed over to the ex-combatants in the municipality of Dabeiba. It is estimated that in Antioquia, 80 per cent of the population was caught up in Colombia’s armed conflict. Historically, the region served as a stronghold for numerous armed groups that were strengthened by illegal economies – illegal mining and illicit crop cultivation.

As all those who UN News spoke to for this article have shown us, peace – and family – are made up of many elements: trust, reconciliation, reintegration, forgiveness, and hard work.

Since the signing of the peace agreement, the UN Verification Mission in Colombia, alongside various UN agencies and Offices, has been accompanying the Llano Grande family on its journey, making it possible for the words in the accord to take root.

This support has been fundamental.

For Mr. Peña because “it has prevented the Colombian Government from doing whatever it wanted with the Accords”.

For Ms. Segura, because “the community has given me a new home”.

For Ms. Cardona because she has started work in her Arepas factory.

For Mr. Zapata and Ms. Oquendo because they are making hands-on decisions at their clothing workshop.

And for Ms. Lopez, because she has provided the music programmes, computers, and desks for the children at her school.

All in all, with the support of the UN, some 15 projects have been launched – ranging from soap manufacturing to fish farming, to education, clothes-making, livestock, and agriculture.

Some promises not met

But like the winding paths that cut through the verdant, heavily forested mountains of Llano Grande, the road to peace has many twists and turns, and takes determination reach the desired destination.

Indeed, both Mr. Zapata Efraím and Mr. Peña point out that “some aims of the peace deal have been accomplished while others have not”. Both noted some key actions have yet to be taken by the Government in the areas of housing, land, and food.

At the same time, many projects in Llano Grande are stalled due to lack of funds or technical follow-up, and in some cases, even due to a lack of commitment from the ex-combatants. Moreover, since April 2021, there have been persistent delays and reductions in the food supply, causing unrest and doubts about the long-term sustainability of the local-level reintegration and reconciliation efforts.

Llano Grande and communities like it have made strides in the wake of the peace deal, but in other places, there is still much work to be done.

Not too far from Llano Grande is the municipality of Apartadó, where the Government will hold the ceremony to commemorate the fifth anniversary of the signing of the Peace Accords, which the UN Secretary-General will attend.

There, the Mayor’s Office has begun construction of a “fundamental highway to connect the rural areas (where the ex-combatants are) with the city”, but currently, there are no resources to finish the project.

And some members of the municipality have cautioned that although there is no conflict between ex-combatants, civilians, military and paramilitaries, there is no reconciliation either; rather, “each one does his own thing without messing with the other,” UN News was told.

In the same department of Antioquia, the Ombudsman’s Office has issued 31 alerts related to homicides, attacks, threats, displacement and stigmatization of former combatants. Since 2017, the department has registered 30 homicides and four disappearances, the vast majority of them men.

Finally, in other parts of Colombia, such as the department of Chocó, things are reportedly more serious, and the UN Human Rights Office (OHCHR) indicated this past Thursday that the situation is “alarming” and that “serious violations” are being committed.

Guterres in Colombia

During his visit, Secretary-General António Guterres will meet with Colombian President Iván Duque and other Government officials, as well as with leaders of the former FARC-EP guerilla movement.

He will attend commemorative events and observe peacebuilding and reconciliation efforts involving former combatants, communities, and authorities. Mr. Guterres is also expected to meet with heads of the transitional justice system, victims of the armed conflict, and leaders of Colombian civil society, including women, youth, indigenous and Afro-Colombian representatives, as well as human rights and climate activists.

Through his visit, the Secretary-General will take stock of the major achievements of the peace process, as well as the outstanding challenges. He plans to convey a strong message of encouragement for the continued implementation of this far-reaching and transformative Peace Agreement for the benefit of all Colombians.

This UN News article was produced in collaboration with the United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia.