Most of Indonesia’s provinces and dozens of cities and regencies impose discriminatory and abusive dress codes on women and girls, Human Rights Watch said today. The harmful impact of these regulations is evident in the personal accounts of Indonesian women – as schoolgirls, teachers, doctors, and the like – collected below.

The Indonesian Home Affairs Ministry, which supervises local governments, should invalidate those local decrees, more than 60 of which are in effect across the country. The central government, however, has no legal authority to revoke local laws, such as the 2004 dress code in Aceh province that was inspired by Sharia, or Islamic law. But government rules nonetheless authorize the Home Affairs Ministry to nullify local executive orders that contradict national laws and the constitution.

“President Joko Widodo should immediately overturn discriminatory, rights-abusing provincial and local decrees that violate the rights of women and girls,” said Elaine Pearson, acting Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “These decrees do real harm and as a practical matter will only be ended by central government action.”

Local authorities have issued discriminatory decrees as executive orders, starting in 2001 in three regencies, Indramayu and Tasikmalaya in West Java province, and Tanah Datar in West Sumatra. Such restrictive local regulations have appeared and spread rapidly over the last two decades, compelling millions of girls and women in Indonesia to start wearing the jilbab, or hijab, the female headdress covering the hair, neck, and chest. It is usually required in combination with a long skirt and a long sleeve shirt.

The officials who issued the decrees contend the jilbab is mandatory for Muslim women to cover intimate parts of the body, which officials deem to include the hair, arms, and legs, but sometimes also the woman’s body shape. Women and girls face social pressure and threats of possible sanctions unless they comply with the regulations.

Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 100 women who have experienced abuse and often long-term consequences for refusing to wear the jilbab. Human Rights Watch collected the text of the regulations and included them as an annex to a 2021 report. South Sulawesi province authorities adopted the latest decree in August 2021.

The 2021 report documented widespread bullying of girls and women to force them to wear the jilbab, as well as the deep psychological distress the bullying can cause. In at least 24 of the country’s 34 provinces, girls who did not comply were forced to leave school or withdrew under pressure, while some female civil servants, including teachers, doctors, school principals, and university lecturers, lost their jobs or felt compelled to resign.

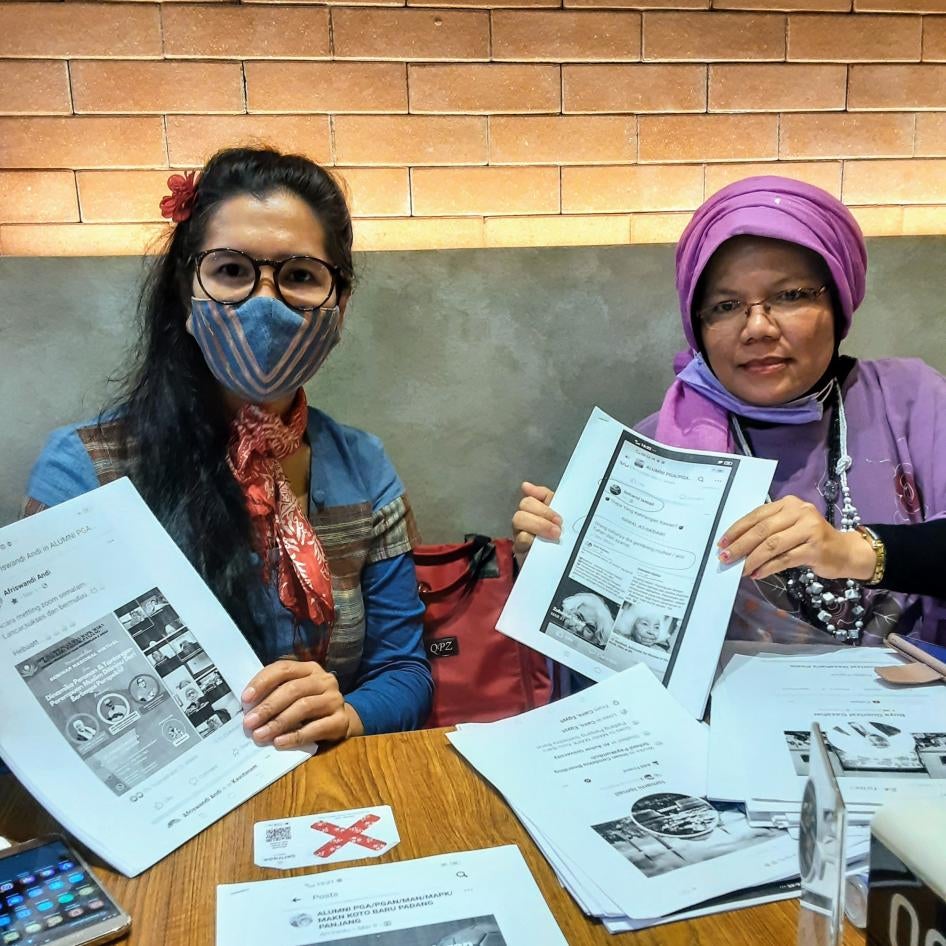

Bullying and intimidation to wear the jilbab also takes place on social media. In two cases, Human Rights Watch documented threats of violence conveyed via Facebook. Human Rights Watch interviews revealed that intimidating and threatening messages have also been sent on messaging apps, such as WhatsApp.

Zubaidah Djohar, a poet, and an alumna of an Islamic boarding school in Padang Panjang, West Sumatra, received death threats that promised “hacking” and “poisoning” after having a theological argument about the jilbab with Gusrizal Gazahar, the chairman of the Indonesian Ulama Council in West Sumatra, on February 28, 2021. Her colleague Deni Rahayu also received death threats, mostly from members of a Facebook group of school alumni. Both reported the threats to the police, but there is no indication police meaningfully investigated the complaints.

They also reported the threats to Facebook but received no response. Human Rights Watch sent extensive documentation of the abusive online behavior to Facebook in April 2021. Facebook responded in August 2021, saying that it “reported the speech to one of [its] escalation channels,” but provided no information on the outcome. In April 2022, after multiple requests for updates, a Facebook staff member based in Singapore offered to meet Djohar during a vacation in Jakarta, which Djohar declined. Facebook has not said what it was doing about the abuse.

Nearly 150,000 schools in Indonesia’s 24 Muslim-majority provinces currently enforce mandatory jilbab rules, based on both local and national regulations. In some conservative Muslim areas such as Aceh and West Sumatra, even non-Muslim girls have also been forced to wear the jilbab.

In 2012 and 2014, Pramuka, the national scout movement that schoolchildren are required to join, and the Education and Culture Ministry, issued dress codes requiring jilbabs for “Muslim girls” from grade 1 through 12, in apparent contradiction of the 1991 ministerial regulation that allows schools to let female students to choose their “special attributes.” The Pramuka and Education Ministry nationwide regulations strengthen and reinforce the local decrees. Schools usually require students to wear the Pramuka uniform once a week.

In February 2021, Education and Culture Minister Nadiem Makarim, and two other ministers, amended the 2014 regulation to specify that schoolgirls are free to choose whether to wear the jilbab. Makarim said the regulation was being used to bully schoolgirls and teachers. But in May 2021, the Supreme Court struck down that amendment to the regulation, effectively ruling that girls under age 18 have no right to choose their own clothes. The ruling ended government efforts to give Muslim girls and teachers the freedom to choose what they wear.

More than 800 public figures signed a petition that condemned the decision and asked the Judiciary Commission to review it, saying the regulation was unconstitutional and discriminatory. In June 2021, the Judiciary Commission rejected the petition on a technicality.

International human rights law guarantees the rights to freely manifest one’s religious beliefs, to freedom of expression, and to education without discrimination. Women and girls are entitled to the same rights as men and boys, including to wear what they choose. Any limitations on these rights must be for a legitimate aim and applied in a non-arbitrary and nondiscriminatory manner.

These protections are included in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Convention of the Rights of the Child, and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. Indonesia has ratified each of these international treaties. Mandatory jilbab rules also undermine the right of girls and women to be free “from discriminatory treatment based upon any grounds whatsoever” under article 28(i) of Indonesia’s Constitution.

In 2006, Asma Jahangir, the late United Nations special rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, said that the “use of coercive methods and sanctions applied to individuals who do not wish to wear religious dress or a specific symbol seen as sanctioned by religion” indicates “legislative and administrative actions which typically are incompatible with international human rights laws.”

“The Indonesian government should take urgent action to end the bullying, intimidation, and violence against ordinary Indonesians who dare to discuss the jilbab issue publicly and raise concerns that these local regulations violate rights,” Pearson said. “The government should investigate every incident and hold those responsible accountable so that every woman and girl in Indonesia feels comfortable to dress the way they want without fearing retaliation.”

For additional details and the detailed accounts by the women interviewed, please see below.

Accounts by Indonesian Women

Human Rights Watch spoke with several women about their struggle against the mandatory jilbab regulations in Indonesia. They wrote their accounts, which have been edited for clarity, and published with their final approval.

Anggun Purnawati, a tour guide in Kebumen, Central Java, and follower of the Kejawen Maneges, an ethnic Javanese local religion, said:

We are a family of Kejawen Maneges believers, including my daughter, Gendhis Aurora, 7, who is a second grader at a state elementary school in Waluya village, Kebumen. We believe that Kejawen Maneges women and girls do not need to wear the jilbab.

At her school, Gendhis has difficulties. School uniform regulations require a jilbab, a long-sleeve shirt and a long skirt. No other choice. Gendhis does not want to wear the jilbab, for both religious reasons as well as health. Gendhis often gets ridiculed and even scorned by her school friends. She is often taunted that she will “end up in hell.” She is often bullied for not wearing a hijab. Several teachers also often ask her to come forward, in front of the class, to be questioned about her reason for not wearing the hijab. We are also often questioned because she does not recite the Quran and participate in Islamic prayer.

Widiya Hastuti, 24, a student at the University of North Sumatra, Medan, from Bener Meriah, Aceh, said:

Since I was a child in Aceh, I was told that women must cover their aurat [intimate parts] from head to toe. I’m not that obedient. I sometimes took off my jilbab and wore shorts when I left our home. The distance was close. I was afraid that the Sharia police would arrest me if I went too far. My parents consequently became the subject of gossip. Some of my cousins called me a thug. My parents often warned me, not because they wanted me to wear the jilbab, but because they couldn’t stand the gossiping.

In 2016, I moved to Medan, North Sumatra, for my university studies. I felt freer to express myself, wear what I want to wear. My mother never protested. But many people are curious. They ask: “Why are you, an Acehnese girl, not wearing the jilbab?” Or, “When you go back to Aceh, don’t you wear the hijab?” The answer is, when I return to Aceh, I do not dare to take off my jilbab. The Acehnese people are becoming increasingly judgmental.

Siti Rokhani, lecturer in public health, Way Jepara, Lampung province, Sumatra Island, said:

The problem with my daughter started during her high school orientation week at SMAN 1 East Lampung [in July 2020]. My daughter wore her school uniform without a jilbab. The orientation committee asked her, “What is your religion?”

She answered, “Islam.” The committee said that all Muslim students must wear the jilbab.

The next day my daughter did not wear the jilbab. The bullying started. She was called immoral, looked at with contempt. Some students recited sentences from the Hadith [sayings of the Prophet Mohammed] in their WhatsApp groups that they believe [specify] the dress code for Muslim women, very far from what we believe in our family. My daughter cried hysterically every time I got home [after work], asking me to move her out of that school. I was sad. It was constant bullying.

My daughter lost her confidence, felt pressured, and had her rights abused. I talked to her and decided to visit the school, meeting her teachers and the orientation committee. I wanted to make sure that the school uniform rules were based on the Ministry of Education regulation.

[I found out] the school has no rule that requires female Muslim students to wear the jilbab. The mandatory jilbab happened because of “an appeal” from Islamic class teachers. It became [part of] the school culture. Education inspectors visited the school in 2021, talking and making the teachers agree that there should be no more bullying and intimidation against schoolgirls who do not wear headscarves.

Dina Fitriya, state schoolteacher from Caracas village, Cilimus sub-district, Kuningan regency, West Java province, said:

Both my parents are teachers. My mother, Ipah Maripah, is a teacher at primary school SD Negeri 1 Caracas. My father, Zubaedi Djawahir, is a teacher at a madrasah [Islamic boarding school] in Cilimus that belongs to the Union of the Islamic Community (Persatuan Ummat Islam, PUI). My father has also served as PUI chairman and secretary of the committee for the construction of the Caracas and Cilimus mosques.

In 2000, my father and some of his followers were summoned by dozens of Islamic religious leaders to a meeting at the Ayong Linggarjati Hotel. More than 100 people were there. The invitation was to have a dialogue, but there were a lot of accusations that my father had committed heresy. He opposed some interpretations of Islam that he considers not practical for Indonesians. The Indonesian Ulema Council later issued a fatwa that he had deviated from Islamic teaching. He was [told he was] not welcome to lecture at any mosque in Kuningan [the area where the family lived]. But my father did not stop, getting even more followers.

On January 20, 2010, my father’s house was attacked and damaged. The attackers shouted “Allahu Akbar” while attacking my father’s house. They pelted the house with stones, shouting “kick out these people.” Our family was forced to flee to Jakarta. When I later took our things to move to a rented house in another area in Kuningan, I was intimidated, starting with men throwing nails on the road so that the trucks carrying our goods could not pass, and then blocking the road with fallen trees. In February 2010, the Indonesian Ulema Council in Kuningan regency issued a new fatwa [religious order] stating that my father was “blasphemous.”

He did not back off. In 2011, my father started to talk about the jilbab not being an obligation, first to his family members, including his children, and then he announced it to the public in 2019. The pressure and intimidation against us were getting stronger.

I started wearing the jilbab in 1991 when I was in fifth grade. In 2011, I decided not to wear a headscarf anywhere but at school, all my ID cards are with hijab-wearing photos. I removed the jilbab because of his clarification that the jilbab is just a [part of] culture. It is not the Islamic Sharia. I also don’t want to be part of the people who are campaigning for jilbabization. In 2013, my extended family moved from Jakarta to Cirebon, the city next to Kuningan. But other incidents still happen to our family and my father’s followers.

Nisa Alwis, author of Puber Beragama di Negeriku (“Religious Puberty in My Country”) and a manager at an Islamic boarding school in Pandeglang, a city in Banten province in western Java, said:

I started to wear the jilbab when I graduated from elementary school and entered an Islamic boarding school in 1986. I continued to wear it until I finished my undergraduate and graduate studies [in 2004]. We used to have open discussions, also about philosophy, when I was a graduate student at Flinders University, Australia, but it didn’t occur to us to take off the jilbab. The code of ethics that had been instilled in me for two decades was binding: there’s no debate about the jilbab. We were socialized that the headscarf is good, let’s all wear the jilbab, if you take it off it’s not good. But I didn’t see this as divine guidance or believe that those who don’t wear the jilbab have a lower level of faith. But still to remove it is a big “no.”

This kept going on until political Islam was rising in Jakarta. I was fed up with the attitude of these so-called Islam defenders. Their attitude and behavior are difficult to accept. The ethical values in this country have shifted along with the bombastic religious jargon. The pace of fanaticism is almost unstoppable, and jilbabization is the gateway to this religious symbolism. Women like me, as well as my children, bear the risks and burdens for a primordial identity that has no end. If our dress code is being dictated, how can women be free with other life choices? If women are weakened, their countrymen will be affected.

I finally took off my jilbab, very slowly, like stages of therapy, by switching to a scarf and kebaya, traditional dress, or a regular dress to recall the memories of the 1980s. I enjoy having debates, but if I am bullied or ridiculed, I try to be patient. I need support from family and close friends. I [took it off] hoping more people would wake up. Religious fanaticism has various forms as well as layers and by wearing the mandatory jilbab, we are exposed [to fanaticism].

The Islamic rules on aurat and jilbab are always based on the interpretation of scholars and it can change from time to time. The view in the Usul Fiqh [philosophy of Islamic law] regarding the jilbab is flexible: “Everything is permissible unless there is a proposition that forbids it.”

Nowhere in the Quran does it say that hair is a disgrace or that jilbab is mandatory. Clothing is just the wrap, the look, not the essence. For hundreds of years, our scholars have not prohibited people from dancing, performing arts, wearing various beauty ornaments, and traditional clothes in Indonesia. But now people are forced to change and leave? Do not let us become a confused nation because we are uprooted from our cultural roots.

Sheilana Nugraha, 25, a graduate student at Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta, said:

Since grade four, my stepmother forced me to wear the jilbab. The atmosphere at home was not healthy, my father often left, thinking everything was fine. In reality, it was really tough.

I entered SMAN 2 Sragen [high school] in 2012 and was asked to wear a headscarf at school. In 2013, a woman hit me with her motorcycle, leaving me temporarily paralyzed. I went to live with my biological mother who lives near SMAN 2.

My birth mother is Christian. My father is Muslim. I took off my jilbab, wearing short-sleeved shirts to school, although my mother still took me to Islamic prayer and study sessions. I was the only Muslim student who did not wear the jilbab at the school. There were Christian students, the number was small, fewer than 10 people in the school, and none of them wore headscarves.

Once [in first year of high school in 2012] I was approached by a history teacher, a woman wearing a headscarf, who was also my neighbor. She scolded me, swearing that I “wouldn’t be successful without the jilbab and would go to hell.” I cried, felt humiliated, and this was witnessed by many students, since it took place in front of the class near the whiteboard and the classroom door. I was shamed. I was crying, depressed.

Four days in a row [in 2012], three female teachers (biology, mathematics, French) plus a male Islamic religion teacher bullied me. The Islamic religion teacher did not make me cry but he was sarcastic. The math teacher was also my homeroom teacher. My grades were affected, screwed up [by the resulting psychological distress]. The principal did nothing to protect me.

In 2014, the history teacher scolded me again, and I looked down and cried. He hit me on the head at school. This occurred often. The chemistry teacher made my report card grades drop. He often did not talk about chemistry in class, but about my jilbab.

I graduated in 2015 and was accepted into the biology faculty at Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta. In 2020, when I was preparing to graduate, I was asked to submit a photo for my bachelor’s certificate. An administrative staff member sent a message asking why I was not wearing a jilbab in my photo. “You want to stick this on your certificate? Why aren’t you wearing a headscarf?” said the staff member. He said all my friends wear jilbab. He asked me to think again, and gave me a week to do so. He continued to pressure me to use a jilbab photo, writing via WhatsApp, but I declined.

Ruhadie Bae, small business owner, Cirebon, said:

My family are Muslims. My eldest daughter, Keyla Aleyda Nirvana Putri, attends high school SMA 1 Babakan in Cirebon. My second daughter, Cleonara Aura Nareswari, studies at SMPN 1 Babakan [middle school] in Cirebon.

We understand that there is not a single commandment in the Quran regarding the mandatory jilbab. I learned from the Muslim cleric Zubaedi Djawahir in 2016 that the Quran directs us to be closer to our local culture. We as a family do not want to be false to this principle. But at school, my daughters are pressured to wear the jilbab.

We believe a Muslim in Java should be close to the kebaya. God created diversity. God teaches us to love our own country, our own culture.

My daughters always get bullied from their teachers or friends. They say: “Hey, you’re a Christian, right? Why are you not wearing the jilbab? Okay, you wear the jilbab only in Islam class, right?” But we didn’t budge.

I went to school and spoke to each of their homeroom teachers. Both schools say my daughters have the freedom to choose. The homeroom teachers are very supportive. But there are other teachers who bully my daughters. And bullying from classmates is always there. Thankfully, my daughters have pleasant personalities. They have many friends who defend them.

Henny Supolo Sitepu, chairwoman of the Teachers’ Light Foundation, Jakarta, said:

The Teachers’ Light Foundation regularly provides training programs on classroom management for state schools. Since 2007, I have been receiving frequent complaints from female teachers regarding the “obligation to wear the jilbab.” There are no written rules. The teachers say they face heavy pressure because the jilbab is associated with morality. Not wearing the jilbab is considered un-Islamic, not a good example for students.

I remember two cases. A teacher was considered to have teased the principal for not wearing a headscarf, and a different teacher [who did not wear a headscarf in a different school] was not given a school uniform. However, the complaints were conveyed in a whisper. And they told me I couldn’t speak publicly about the cases. The fear among teachers is very deep.

Multiple local rules that make the jilbab mandatory are accompanied with sanctions. Our schools uncritically absorb what is happening in public. It shows a trend in Indonesia: when clothing is associated with Islam, it is as if it is taboo to question it.

Police and Social Media Inaction on Hijab Intimidation and Threats

Most women and girls interviewed said they had not reported abuse they endured but tried to handle it themselves. Some blame themselves, saying they believe they are not Islamic enough, using the phrase: “I have not received the hidayah [holy guidance].” But some did report it to the Education Ministry or to the police.

A group of men attacked Ade Armando, a Cokro TV commentator, who had broadcast a report about hijab requirements for women and girls, while he was attending a rally outside the national parliament on April 11, 2022. The police arrested six men, including Arif Pandiani, who had allegedly “provoked the mob” to attack Armando. Pandiani later made a video that falsely claimed that Armando had died. Armando suffered brain injuries, resulting in hemorrhaging, and was hospitalized for five weeks, while his family moved temporarily out of their house in Depok, a suburb south of Jakarta, for their safety. The men are now awaiting trial.

Karna Wijaya, a professor at the Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta, then posted a Facebook comment calling for Armando and his TV colleagues, including Nong Darol Mahmada and her husband, Guntur Romli, “to be slaughtered.” Romli reported Wijaya to the police for hate speech. While the police confirmed they received Romli’s report, they have not summoned him for questioning.

Djohar said she reported the abusive comments on her Facebook page to the national police in Jakarta, in March 2021. She posted photos on her Facebook page of her visit to the police station. She said the police did not investigate, but she noted that filing the complaint at least prompted people who had been sending abusive comments to stop posting on her Facebook page.

Hijab Regulations Elsewhere in Indonesia

The hijab issue and women’s dress has prompted a global debate in Muslim-majority countries, such as Indonesia, as well as in countries where Muslims constitute a significant minority population.

Most of Indonesia’s 34 provinces are majority-Muslim. Bali is predominantly Hindu, four provinces are majority Christian, and another five provinces are balanced almost 50-50 between Muslims and Christians.

In Indonesia, the mandatory hijab rule did not exist until after the fall of President Suharto in 1998. Many conservative Muslim groups advocated the introduction of mandatory hijab rules in Indonesia, starting from conservative provinces like West Java, West Sumatra, and Aceh, using the regional autonomy drive in, post-Suharto Indonesia, to win political support for the measures.

Saiful Mujani, a lecturer at the Jakarta Islamic State University, wrote, “When I was growing up in the 1970s, Muslim students rarely wore the jilbab. Now many parties claim that wearing the jilbab, and even the veil, is an obligation that is ordered in the Quran. Did the verses related to the jilbab and veil does not enter Indonesia before?”

Mujani wrote on his Facebook page in February that, “Most likely this new interpretation of these verses appeared after the Iranian Revolution in 1979, or later because the influence of Arab fashion that is getting stronger in Indonesia.”

Mujani continued: “Whether it is mandatory or not to wear the jilbab is a matter of mere human interpretation … and all of them are open to error. No public institutions such as government offices, state schools or state madrasas, state universities, even state Islamic universities, should require the jilbab. To wear the jilbab or not should be left to the subjective choice of each Muslim woman.

In February 2021, after a complaint from the father of a Christian secondary school student in Padang, West Sumatra, went viral on social media, Education Minister Nadiem Makarim, Home Affairs Minister Tito Karnavian, and Religious Affairs Minister Yaqut Cholil Qoumas signed a decree that allows any student or female teacher to choose whether to wear the hijab in school.”

However, on May 3, 2021, in a blow to women’s rights and children’s rights, the Supreme Court canceled that regulation after a petition from a local group called Lembaga Kerapatan Adat Alam Minangkabau in Padang, West Sumatra. The panel of three male judges, Irfan Fachruddin, Is Sudaryono, and H. Yulius, ruled that the government’s regulation violated four national laws and that children under age 18 have no right to choose their clothes.

Several Muslim scholars in Indonesia who have argued the jilbab should not be mandatory have been bullied and faced violence.

In January 2022, Nisa Alwis, a Muslim scholar who helps manage her family’s Islamic boarding school in Pandeglang, Banten province, wrote on her Facebook page, “Among the biggest hoaxes this century is the thinking that showing our hair is indecent, that women’s hair bring people to hell. No need to overdo it. We must think about our children and grandchildren. Alwis said she has frequently received messages on her Facebook page since that time, bullying and intimidating her.

Lack of Staff Accountability for School-Based Abuses

In 2021, after Human Rights Watch published its report on the harm to women and girls because of mandatory jilbab rules, the Education Ministry sent inspectors to visit schools in several provinces. The inspectors persuaded school principals to take down signs with the mandatory jilbab announcement. The inspectors also asked principals not to pressure schoolgirls to wear the jilbab. However, no principal or teacher was penalized. The ministry also set up a hotline service to receive reports of bullying and intimidation.

In January 2021, at SMKN2 state high school in Padang, after a video on jilbab went viral and a school inspector visited, the school stopped pressuring Christian students to wear the mandatory jilbab and long-sleeve shirts. The video, uploaded on Facebook, was made by the father of a girl who attended the school.

The video recorded a teacher pressuring the father to make his daughter, who is a Christian, wear a jilbab at school. He asked the teacher, “Is it advice or an order?” The teacher replied, “This is the school regulation at SMKN2 Padang. This is a mandatory jilbab rule.” He also posted a photo of the school’s letter to him stating that his daughter needs to wear a jilbab. The media reported the situation widely. But officials did not penalize the school principal, and the school is still pressuring Muslim girls to wear the jilbab.

In February 2019, at SMPN8 state high school in Yogyakarta, a mother reported the school to the National Ombudsman Office in Jakarta because the school principal, Islam religion teachers, and other students had routinely bullied her daughter to wear a jilbab. The Ombudsman Office sent an inspector and asked the school to end the abusive practice. The schoolgirl was allowed not to wear the jilbab. She became the only Muslim girl not wearing the jilbab in that school. But school officials were not penalized.

A 29-year-old piano teacher at a state school in Bantul, Yogyakarta told Human Rights Watch that she gradually overcame the deep physical and psychological pain the jilbab rule had caused her. She no longer had to wear the jilbab after the school inspectors visited the school in April 2021. But Education Ministry officials did not penalize the principal or other school staff who she said bullied her.

Some women who were bullied set up a monthly Forum for the Jilbab Bullying and Intimidation Survivors to listen to other victims and share their own experiences. They have discussed overcoming their psychological trauma and gaining confidence to stand up and advocate for rights-respecting reforms. Others wear traditional clothing instead as a form of protest against mandatory hijab rules and to preserve Indonesian culture.