The economic cost of the pandemic for sub-Saharan Africa is unprecedented, and the region continues to grapple with the pandemic.

Related Links

Although the outlook for the region has improved since October 2020, the -1.9 percent contraction in 2020 remains the worst performance on record. Sub-Saharan Africa will be the world’s slowest growing region in 2021, and risks falling further behind as the global economy rebounds. Our latestRegional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa takes a close look at the issues.

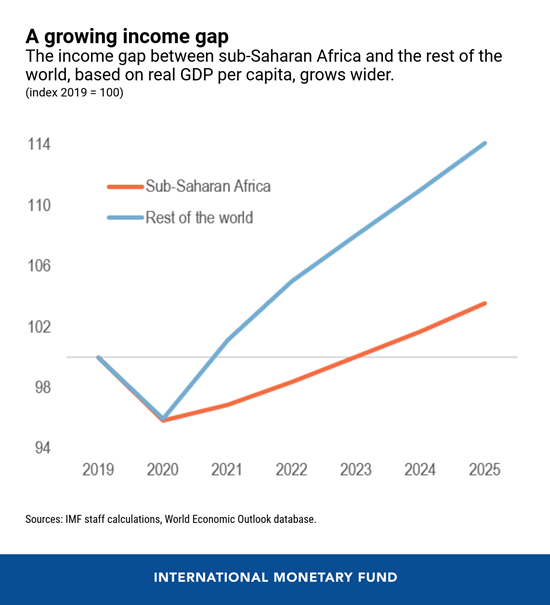

On current forecasts, per capita GDP in many countries is not expected to reach pre-crisis levels until the end of 2025. Limited access to vaccines and the region’s lack of fiscal space are expected to weigh on the outlook. As a result, the gap between sub-Saharan Africa’s growth and the rest of the world is expected to widen further over the next five years.

To support future growth and transformative reforms, international help will be required to meet the $245 billion in additional external funding needs that sub-Saharan Africa’s poorest countries face over the next five years or $425 billion for the region as a whole. The extension of the Group of Twenty debt-service initiative to December 2021 and the new Common Framework on debt can be helpful in this regard. The proposed $650 billion special drawing rights allocation would provide about $23 billion to sub-Saharan African countries to help boost liquidity and fight the pandemic. But meeting these needs will require contributions from all potential sources, including the international financial institutions and private sector, and debt-neutral support from donors.

The crisis is not over anywhere until is over everywhere. A global effort will be required to give sub-Saharan Africa a fair shot at a durable recovery and a prosperous future.

Here are six charts that tell the story:

- Sub-Saharan Africa will be the world’s slowest growing region in 2021. The region is projected to grow by 3.4 percent, buoyed by the global recovery, increased trade, higher commodity prices, and a resumption of capital inflows. However, the recovery in sub-Saharan Africa is expected to lag behind the rest of the world with a cumulative per capita GDP growth over the 2020-25 period projected at 3.6 percent, substantially lower than in the rest of the world (14 percent).

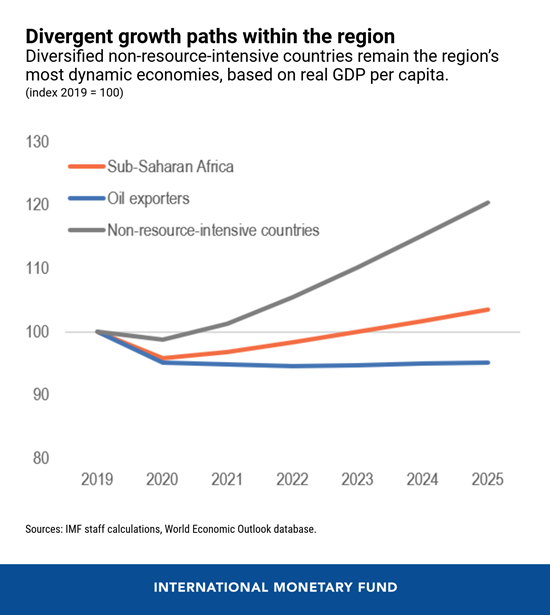

Within the region, the divergence that existed between resource intensive and non-resource intensive countries will persist. Non-resource dependent countries are forecast to see average per capita incomes rise by 21.6 percent by 2025. Oil exporters, which are some of the more populous countries in the region, will have no gains in per capita income over this period.

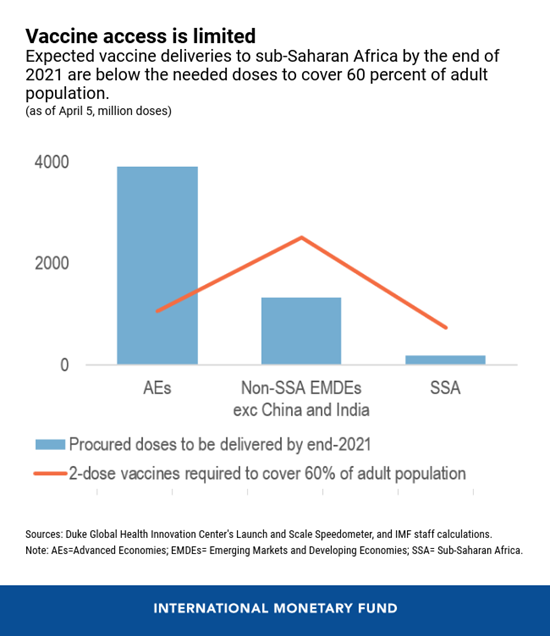

- Lower access to vaccines, slower vaccine rollout, and potentially high cost of vaccinations are holding back the recovery in sub-Saharan Africa. Some advanced economies have secured enough vaccine doses to cover their own populations many times over, while many countries in sub-Saharan Africa will be struggling to simply vaccinate their essential frontline workers this year. Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for 15 percent of the global population, but as of April 5, only 0.5 percent of all administered doses globally were in sub-Saharan African countries. Thirty-eight out of 45 countries in the region rely on COVAX, an international initiative to ensure equitable vaccine distribution, and the African Union for access to vaccines. COVAX has started delivering doses to the region, but supplies are limited.

The success of the vaccine rollout also depends crucially on the distribution infrastructure (for example, cold chain storage), which many countries in the region lack. At the same time, the cost of vaccinating 60 percent of population could be prohibitively high for some countries, reaching 50 percent of 2018 health expenditures in Democratic Republic of the Congo and The Gambia. Vaccination cost is more than 2 percent of GDP for a quarter of countries in the region. This could double or triple if there is a need for booster shots. The international community could play a crucial role by eliminating restrictions on the dissemination of vaccines or medical equipment, fully funding multilateral facilities such as COVAX, and quickly redistributing excess vaccine doses.

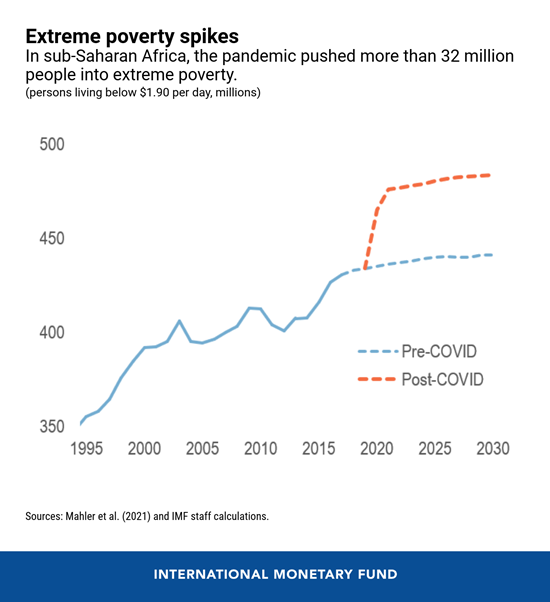

- The COVID-19 crisis is expected to undo years of economic and social progress and leave lasting scars on the region’s economies. The number of people in sub-Saharan Africa living in extreme poverty is projected to have increased by more than 32 million in 2020; the number of missed school days is more than four times the level in advanced economies; and employment fell by around 8.5 percent in 2020. In terms of livelihoods, per capita income has returned to 2013 levels. Stronger social safety nets are needed to channel support quickly and efficiently to those most in need to prevent permanent scarring.

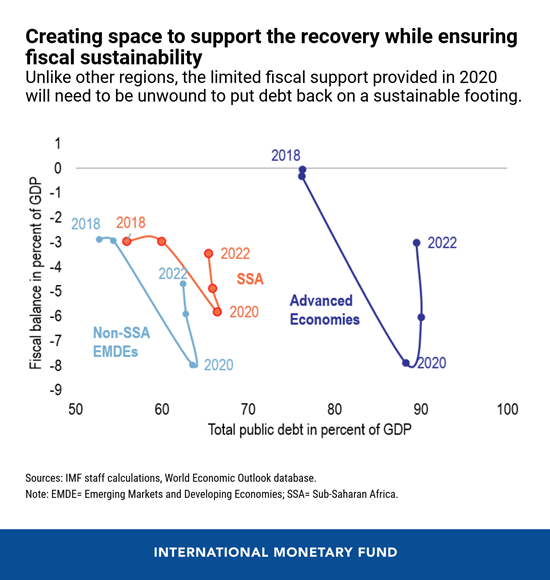

- To create space to support the recovery, the health of public and private balance sheets needs to be restored. Sub-Saharan African countries entered the crisis with elevated debt vulnerabilities and less room to spend. Pandemic-related fiscal packages in the region averaged only 2.6 percent of GDP in 2020, markedly less than the 7.2 percent of GDP advanced economies spent. Yet, public debt increased in sub-Saharan Africa to more than 66 percent of GDP (weighted average of 58 percent) in 2020, the highest level in almost 15 years, owing largely to declining revenues and output. Thus, 17 countries, representing around one-quarter of the region’s GDP, or 17 percent of the region’s debt stock, are now either at high risk of debt distress or are already in distress.

Private sector balance sheets were also hit hard by the pandemic. Firms’ monthly sales plummeted by 40-80 percent in 2020 compared to the pre-crisis levels. Between 50 and 80 percent of surveyed households reported income losses at the height of the first wave of the pandemic as containment measures were put in place. The non-performing loan ratio has to date increased only modestly within the region due to the regulatory forbearance measures taken by countries during the crisis.

- Unleashing sub-Saharan Africa’s considerable potential requires bold and transformative reforms.

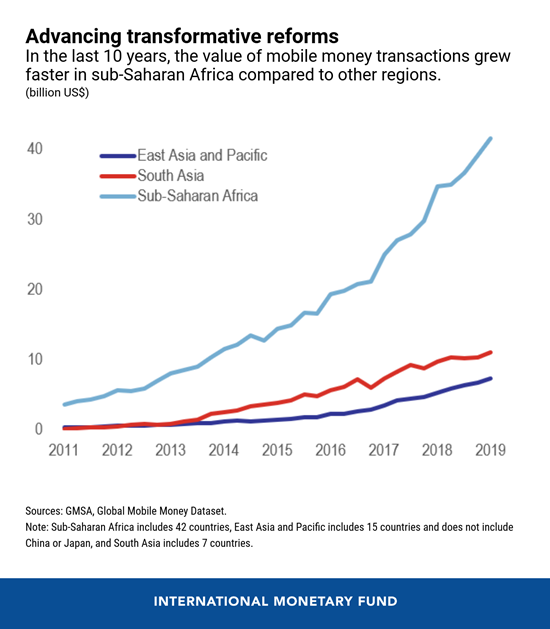

Every day, more than 90,000 new users in sub-Saharan Africa connect to the internet for the first time. Capitalizing on the digital revolution would enhance sub-Saharan Africa’s resilience and efficiency, expand access to global markets, improve public service delivery, boost transparency and accountability, and foster the creation of new jobs.

Every week, economies in sub-Saharan Africa export about $6.5 billion in merchandise goods. But only about one-fifth of those exports are destined for other countries in the region. Implementing the new African Continental Free Trade Area would not only reduce Africa’s vulnerability to global disruptions, but also boost regional competition, improve productivity, attract foreign investment, and promote food security.

Every year, 20 million new job seekers enter the labor market in sub-Saharan Africa, one of the region’s greatest strengths over the long term. Within the next 10–15 years, nearly one in two new entrants into the global labor force will come from sub-Saharan Africa, and with an increasingly urbanized population, transformative reforms to strengthen social protection systems, promote digitalization, improve transparency and governance, and mitigate climate change would help boost consumption in the region which could also drive the global demand for goods and services. Policymakers will need to create more fiscal space to support these reforms by mobilizing domestic revenue, enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of spending, and managing public debt vulnerabilities.